Unconventional Wisdom from John Kominicki: 60 years on, we’ve discovered that size, at least when it comes to housing, really matters

History has anointed Bill Levitt the king of suburbia, but the crown might have as easily gone to Walter Turnbull Shirley, a Brooklyn-born song promoter and wannabe impresario who turned to selling Long Island’s pastoral charm to the masses in the late 1930s.

As Shirley told the story, he smooth-talked his way into a meeting with William K. Vanderbilt II, grandson of the railroad titan and one of the largest landowners on the Island.

Willy K., as he was known, had been burdened with an inheritance worth $1.5 billion today, but decades of carefree spending, the dawn of the federal income tax and the long toll of the Depression had begun to convince him that money was maybe an object after all.

After unloading his private Motor Parkway racetrack on local municipalities – in lieu of $80,000 in back taxes – Vanderbilt decided to make liquid some of the vast tracts he owned around Lake Ronkonkoma. In 1937, he agreed to sell Shirley 250 acres – with lake views and a mile of Motor Parkway frontage – for the bargain price of $8,000.

(If you’ve doubted Shirley’s skills to this point, Vanderbilt wanted $100,000.)

Thousands rushed to own their share of what was marketed as the “Vanderbilt Estate,” and Shirley quickly acquired another 750 of Willy’s acres, then thousands more in Smithtown, Islip and Mastic. Standard 0ffer: A quarter acre for $99, put $10 down and pay $1 per week.

If you wanted an actual house on your property, Shirley sent you to the Lido Construction Co., run by Alfred Parr and, later, his kid brother, Ron. In 1949, their $4,995 starter house was almost identical to the Levitt homes being built in Nassau County – boxy Cape Cods with living room, two bedrooms, a kitchen and bathroom that totaled less than 750 square feet. There was space to grow in an “expansion” attic.

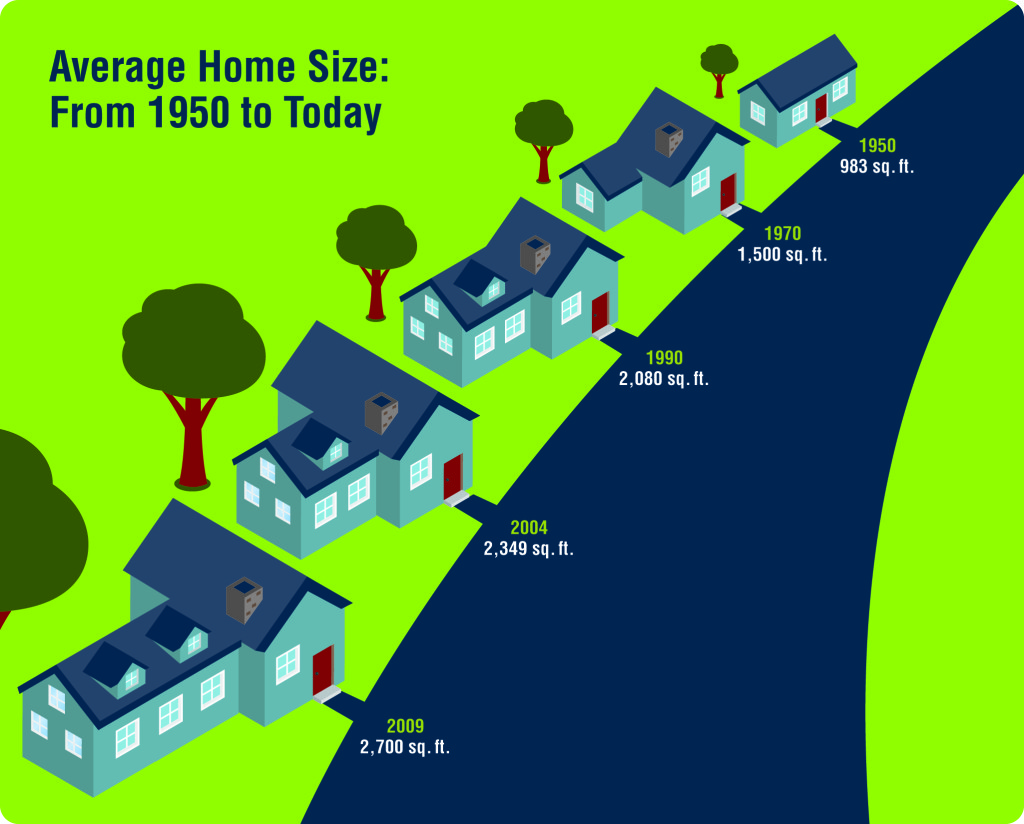

Though significantly smaller than American homes built before the Depression and World War II – the average in 1920 was 1,200 square feet – early post-war homes could be built fast and affordably for returning vets and City residents yearning for suburbia. At peak pace, Levitt was putting up 30 houses a day.

Thanks to FHA loan guarantees that required as little as 3 percent down, houses didn’t remain small for long. Responding to consumer demand, builders like the Parr brothers quickly introduced a larger ranch, then ever-bigger colonials, high ranches and other models.

Long Island municipalities also began regulating the size of new homes, ostensibly to standardize the look and feel of their sprouting subdivisions, although the regulations clearly served to keep out those who couldn’t afford the mandated minimums. The Town of Brookhaven, for one, required a minimum home size of 1,000 square feet beginning in 1953.

By the early 1960s, the Parr brothers’ top sellers were the 1,600-square-foot Mayflower and the 2,200-foot Arlington. They built more than 10,000 houses over the years, at one point consuming half of all the lumber sold in Suffolk County.

America’s love for ever-bigger abodes has not moderated in the years since. Today’s average new home has grown to more than 2,600 square feet, even though the average American household has steadily shrunk, from 3.3 people in 1960 to 2.5 today.

Hindsight, we know, is perfect, and it’s tough to condemn the 1950s zoning boards that sought to do right by our returning World War II vets. But, as we now know, communities find their real strength in diversity, not mandated homogeny.

Long Island would be a vastly more vibrant region today if post-war planners had promoted a much broader range of housing options, including smaller, more affordable houses – and significantly more apartments – that could better accommodate all ages and incomes. Especially the under-30 crowd that has been leaving the Island en mass to find affordable digs elsewhere.

That the 1950s rush to build homes for young GIs spawned the loss of the Island’s young population today is perhaps the region’s greatest irony.

Second is how slow we’ve been in doing anything about it.