Unconventional Wisdom from John Kominicki: It’s All about Keeping Our Future on Track

America’s first railroad was the Baltimore & Ohio, chartered in 1827 to compete with New York’s Erie Canal in the lucrative business of shipping goods westward.

Baltimore was America’s third-largest city then – with designs on getting bigger – and the new railway was celebrated with parades and fireworks and a ceremonial groundbreaking at which the 91-year-old Charles Carroll, the last living signer of the Declaration of Independence, turned over the first spade.

Virtually every resident of the city owned at least one share in the new enterprise, which was wildly popular and significantly oversubscribed – even though it initially had no planned end point beyond “Ohio.”

Alas, the launch of the B&O was not typical. Early American railroads, though later credited with sparking the Industrial Revolution and providing the lift for manifest destiny, were generally feared and almost always fought over. They were widely considered a threat to the established rural order and a menace to livestock and crops along the tracks.

Humans foolish enough to consider passage would almost certainly die from asphyxiation, which, it was commonly believed, set in at speeds above 20 miles per hour. Many others would surely be killed or maimed by runaway engines, exploding boilers and bolting horses.

But speed quickly won over the skeptics and detractors. In 1831, the Mohawk & Hudson reduced the 40-mile, daylong canal trip between Albany and Schenectady to 16 miles of rail that could be covered in less than an hour.

The Long Island Rail Road, launched in 1832, was also all about speed – getting New Yorkers to Boston at a time when the direct route across southern Connecticut was considered impassable. Since the LIRR’s founders had no interest in servicing the locals, the rails were laid along the mostly unpopulated center of the Island, miles from the region’s coastal communities and any possible protests.

A few forward thinkers saw opportunity in the rail line, however, and pounced. Valentine Hicks, a member of a prominent Quaker family, bought land along the line in 1834 and founded a thriving agricultural hub that grew cucumbers and potatoes for shipping westward. It’s called Hicksville today.

Horticulturalist John Lewis Childs bought up large tracts around what is now Floral Park and built the first American seed catalog company, using the LIRR to distribute nationally. German immigrants Philip Miller and John Christ built a store, hotel and other businesses around the tracks in New Hyde Park, establishing a downtown bustling enough to eventually warrant its own station.

Mineola parlayed its prominence along the rail lines into being named the county seat.

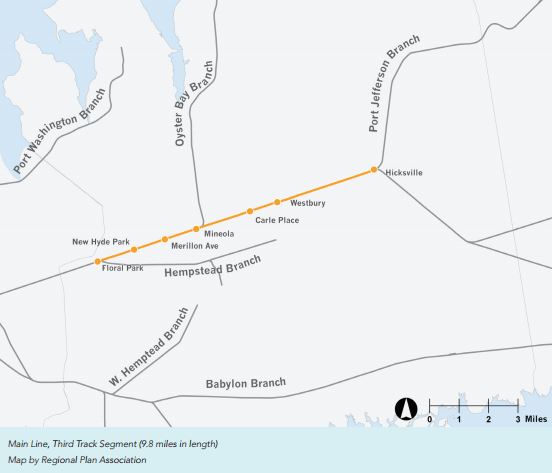

Those same communities have a new role to play in the evolution of the LIRR, this time concerning the addition of a third set of tracks between Hicksville and Floral Park.

The $2 billion third track project would greatly reduce rail congestion in the area and permit east-bound trains during peak hours, opening Long Island jobs to reverse commuters from the NYC boroughs. Hundreds of thousands of commuters would see their daily rides shortened, and there would be increased parking, station upgrades and other enhancements.

Seven at-grade street crossings would be eliminated, significantly improving local traffic and safety. As many as 14,000 permanent jobs would be created.

The plan is overwhelmingly favored by commuters – no surprise – and support from communities along the tracks is growing thanks to a trio of get-the-word-out public meetings and a grass roots coalition that represents 500,000+ Long Islanders.

I’d like to think there’s some good old-fashioned American pride and optimism in there, too, the belief that Long Island and its people are still worth investing in for the future.

Delivering destiny, after all, is what railroads have always done best.