Unconventional Wisdom from John Kominicki: Your Chromosomes Want to Pump You Up

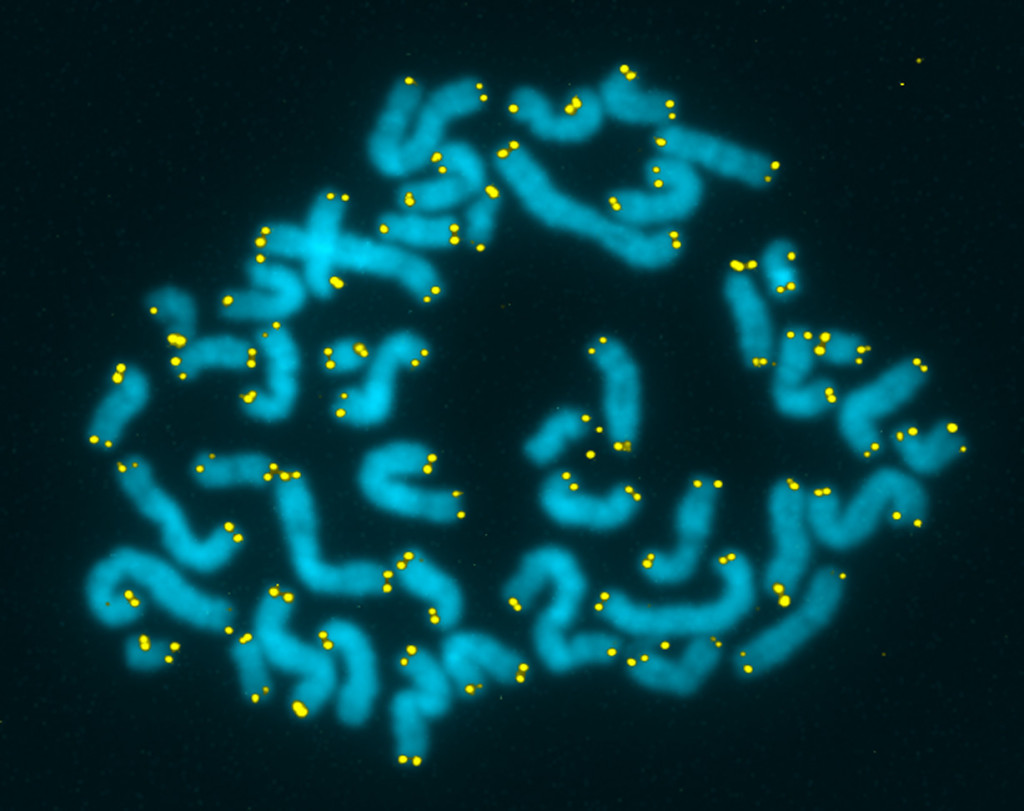

Some of the most interesting genetic research being performed today – including work at our own Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and Stony Brook University – concerns telomeres, the protective caps on the ends of chromosomes, those thread-like strands that store our genetic information.

Very simply put, the longer and more vibrant your telomeres, the better chance you have of avoiding the diseases and conditions that are most likely to kill you before your time, including cancer, diabetes, blood and bone maladies, even Alzheimer’s.

At Stony Brook, a team led by microbiologist Bruce Futcher is studying the role telomeres play in cell health and aging. Cancer, we know, is caused by cell division gone mad, but too little division may be the direct cause of aging, Futcher & Co. believe.

Cold Spring Harbor has been at the forefront of telomere research since the mid-1940s, when future Nobel Prize winner Barbara McClintock isolated the telomere in maize. The lab will host a four-day conference on telomeres – its 10th annual – in May.

Most recently, scientists have established a link between shortened telomeres – and, therefore, shortened lives – and stress and lack of exercise.

There are no clear measures here beyond the most obvious. Exercise is good, more exercise is better. Avoiding stress is great, quitting your crummy job and telling your meddling mother-in-law to stick a sock in it might be downright life extending.

Oh, and meditation might also help, they’ve discovered, so if you assume the lotus position every once in a while, Bob’s your uncle.

So how much longer might you live? Good question. A recent study suggests the body’s ability to generate new cells peters out at around age 115, meaning no amount of telomere coddling will buy you time beyond that. You can, in other words, stop jogging at 114.

The list of living supercentenarians – that is, people over age 110 – seems to confirm just such a finite end to life. The oldest living American as I write this is New Jersey resident Adele Dunlap, who turned 114 on Dec. 12. Only seven Americans have ever lived longer than 115 years, according to the Gerontology Research Group, which tracks and verifies the ages of really old people.

The seven were all women, by the way.

Not all scientists are willing to accept the 115-and-done scenario, especially a University of Liverpool group researching the bowhead whale, a fellow mammal that routinely lives 200 years or longer. The bowhead’s genetics have been sequenced recently, leading scientists to about 80 genes they believe are directly related to longevity. A long-term study, backed by two age-focused foundations, hopes to peek gingerly at genetic modification, the kind of science that has heretofore been reserved for Michael Crichton books.

The questions, of course, abound: Could the genome be manipulated to extend the life of future generations of humans? What are the moral and ethical issues associated with that? Are transgenic stem cells even possible and, if so, wouldn’t they make humans suddenly crave plankton?

The answers are still many years in the future and, being a man, I’m apparently already at a disadvantage. Perhaps I’ll increase the exercising. A little swimming might be prudent.